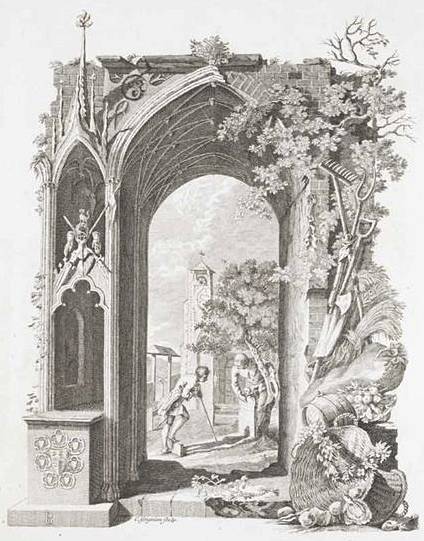

‘Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard’ by Thomas Gray, illustrations by Richard Bentley, London, England, UK, 1751. Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Background

The author

Thomas Gray (1716 – 1771) was born in Cornhill, London and educated first at Eton, where he met Horace Walpole (1717 – 1797), son of the Prime Minister Robert Walpole and the writer of the Gothic novel The Castle of Otranto, and then at Cambridge. Together with Walpole he left for a tour on the Continent, maybe the most remarkable event of his retired and uneventful life, that lasted three years and he ended alone owing to a temporary quarrel with his travel friend. Back to England, he resumed the friendship with Walpole, who would have later helped him to publish in 1751 his Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard, and settled down in Cambridge where, except for some occasional trips to the Lake District, a cult place for the first Romantics to come, he lived for the rest of his life. In 1757 he refused the Laureateship and in 1768 he was appointed Regius Professor of Modern History and Languages at Cambridge, a charge that he partially carried out because of his shyness that always forbade him to give public lectures. At his death in 1771 he was buried in the churchyard of Stoke Poges which, as it is commonly thought, may have inspired his Elegy.

In spite of his deep classical culture, his wide knowledge of both Celtic and Icelandic poetry, meant as expressions of primitive cultures, together with his interest in country life, humble people and meditation made of him, as to the content of his works, one of the many forerunners of the future Romantic movement. Concerning his versification, on the contrary, he was a classicist, convinced as he was that poetical language should be very cultivated, respectful of the classical canons and as distant as possible from the common spoken one. Owing to this permanence of old elements in form side by side with the introduction of new ones in content, Gray is commonly considered as a transitional poet between two great literary movements such as Enlightenment and Romanticism.

The text

Even if this poem belongs chronologically to the Augustan Age, its focus on deep feelings and on a new approach to nature together with a widespread sense of melancholy and a highly meditative mood may easily show the twilight of classicism in poetry that gave way to a transition stage in which both old and new elements can be found side by side. The difficult task of detaching himself from the themes exploited by Pope’s poetic diction, which had already become the only canon of making poetry, together with his convinced rejection of using the common spoken language in poetry, is clearly shown by the long writing time – more than seven years – that this elegy took the writer who had been searching a different poetry both in content and, on a lexical level, in versification. His reaction, however, more than in form, based on the precise pattern of 4-line and alternate-rhyme stanzas of iambic pentameters taken by Dryden and generally modelled on the twenty-fourth ode of Horace’s First Book of Odes, is to be found above all in its setting and themes as well, deeply interwoven one another. The space of the poem is a country churchyard, where the cemetery is the perfect background for the general theme of death pervading the whole composition and the country is both used for the appreciation of nature – seen as a reality made up of earth, trees, animals but of the human work and fatigue too – and for the social focusing on what, by the Romantics to come, would have been called humble rustic life; the time is the twilight, that particular moment of the day later defined as the breaking between the opposed worlds of day and night, when the daylight is slowly fading away while the shadows of darkness are growing up to give way to the dark side of life where a conscious melancholy replaces a mindless joy and a deep meditation takes the place of a careless action. As to themes, death is undoubtedly the most evident one, present as it is from the very title of the poem to the closing Epitaph, and, in the poet’s intention, it is seen both as an event showing the transience of matter, thus giving the chance to meditate on the very meaning of life, and a sort of gigantic levelling power that annihilates the distance among men belonging to different social classes. Nature is the other great theme of the poem and, just like death, She also is observed from two different points of view: at a surface observation the natural imagery, in its quiet and melancholic aspect, in the gentle and peaceful vision, may easily recall to the reader’s mind the taste – typical of the time e.g. in Pope’s Pastorals or Windsor Forest as well – for those Latin pastorals written by poets such as Teocritus or Virgil, but, on a closer sight, the natural element is not a distant and idealized background anymore but a living thing which men have to interact with, often in terms of hardship and physical labour. In the Elegy, the human beings, seen as working men who become forefathers thanks to their sweat and fatigue, are astride Life, represented by their relationship with Nature, and Death, represented by the humble country churchyard with all its fragile witness of past lives. According to its content, the Elegy may be divided into three different parts or moments: 1. the vision of a small country churchyard, with the poor tombs of humble people in a striking contrast between the boasting exequies of the rich, gives the poet the chance to meditate on death, the transience of life and to recall the reader’s attention to the social differences in life that, however, are completely dissolved and annihilated by the levelling power of death (stanzas 1-11); 2. through the contrastive comparison between the humble lot of poor people and the great men’s fortune – emphasized by the presence of Capital Sins such as Ambition, Flattery, Luxury, Pride, etc. – the poet considers how the same lot that forbade humble people to carry out big enterprises prevented them, in the meantime, from committing crimes and links this second part to the first one (stanzas 12-21); 3. the poet’s attention is shifted on himself, thus giving the Elegy a more intimate and personal tone, when he considers his supposed death and subsequent burial in the same churchyard (stanzas 22-29). The Epitaph, the final part of the poem (stanzas 30-32), might easily stand alone as a perfect sum of the author’s life and opinions, as a moral legacy for the world.

The Graveyard School of Poetry

Poetry surely was the literary genre which, introducing new trends in contrast to classicism, best mirrored the conflict between intellect and emotions, reason and feelings, busted out by the second half of the 18th century and culminated in the twilight of Classicism. Since the 1720’s, a strong sense of dissatisfaction with the society born from the Industrial Revolution together with the increasing absence of religious values, in favour of the absolute faith in reason, had led some poets to feel a painful sense of failure and frustration which soon made them felt as dropouts: unable to accept the dominant attitude which considered man as a social being only driven by material needs, disregarding both his soul and feelings, they turned to a more intimate poetry of the spirit but what troubled them most in this rejection, more than content which had naturally sprung up from their personal needs, was the absolute lack of a language able to express their feelings and emotions, their pains and disillusions so that they soon found themselves without any possible communication in a strangers’ land and escaped in nature and in the humble life of country people to find a shelter far from the madding crowd’s ignoble strife. The poets who first gave voice to this change, e.g. J. Thomson, with his long poem The Seasons (1726-1730), and W. Collins, especially in his Ode to Evening (1746), were called elegiac for their pensive mood and the links with Latin works such as Virgil’s Georgics.

Meditation on Nature and Man’s destiny was soon tinged with a sort of melancholy for the transience of life which slowly shifted these poets’ attention from the living world and drew them deeply away into the dark dimension of decay and death where the poetical form which best fitted their mood was still the elegy, meant as a lament for someone’s death, and the space was circumscribed by ruins and tombs thus giving life to what is commonly referred to as the Graveyard School of Poetry, an English phenomenon which paved the way for the Gothic literature and the darkest side of Romanticism. Among the poets who tried to explore the world of the dead, it is important to mention E. Young, who wrote, in blank verse, The Complaint; or Night Thoughts on Life, Death and Immortality (1742-1745), and R. Blair, author of The Grave (1743), a meditation on death imbued with a strong religious devotion, and, maybe, it is not perchance that they both were ministers of the Anglican Church. It was, however, Thomas Gray the one who, with his Elegy, found the best balance in the features and themes of both the elegiac and the graveyard poets.

Elegy Written In A Country Churchyard (1742-1750)

The curfew tolls the knell of parting day,

The lowing herd wind slowly o’er the lea,

The plowman homeward plods his weary way,

And leaves the world to darkness and to me.

Now fades the glimm’ring landscape on the sight,

And all the air a solemn stillness holds,

Save where the beetle wheels his droning flight,

And drowsy tinklings lull the distant folds;

Save that from yonder ivy-mantled tow’r

The moping owl does to the moon complain

Of such, as wand’ring near her secret bow’r,

Molest her ancient solitary reign.

Beneath those rugged elms, that yew-tree’s shade,

Where heaves the turf in many a mould’ring heap,

Each in his narrow cell for ever laid,

The rude forefathers of the hamlet sleep.

The breezy call of incense-breathing Morn,

The swallow twitt’ring from the straw-built shed,

The cock’s shrill clarion, or the echoing horn,

No more shall rouse them from their lowly bed.

For them no more the blazing hearth shall burn,

Or busy housewife ply her evening care:

No children run to lisp their sire’s return,

Or climb his knees the envied kiss to share.

Oft did the harvest to their sickle yield,

Their furrow oft the stubborn glebe has broke;

How jocund did they drive their team afield!

How bow’d the woods beneath their sturdy stroke!

Let not Ambition mock their useful toil,

Their homely joys, and destiny obscure;

Nor Grandeur hear with a disdainful smile

The short and simple annals of the poor.

The boast of heraldry, the pomp of pow’r,

And all that beauty, all that wealth e’er gave,

Awaits alike th’ inevitable hour.

The paths of glory lead but to the grave.

Nor you, ye proud, impute to these the fault,

If Mem’ry o’er their tomb no trophies raise,

Where thro’ the long-drawn aisle and fretted vault

The pealing anthem swells the note of praise.

Can storied urn or animated bust

Back to its mansion call the fleeting breath?

Can Honour’s voice provoke the silent dust,

Or Flatt’ry soothe the dull cold ear of Death?

Perhaps in this neglected spot is laid

Some heart once pregnant with celestial fire;

Hands, that the rod of empire might have sway’d,

Or wak’d to ecstasy the living lyre.

But Knowledge to their eyes her ample page

Rich with the spoils of time did ne’er unroll;

Chill Penury repress’d their noble rage,

And froze the genial current of the soul.

Full many a gem of purest ray serene,

The dark unfathom’d caves of ocean bear:

Full many a flow’r is born to blush unseen,

And waste its sweetness on the desert air.

Some village-Hampden, that with dauntless breast

The little tyrant of his fields withstood;

Some mute inglorious Milton here may rest,

Some Cromwell guiltless of his country’s blood.

Th’ applause of list’ning senates to command,

The threats of pain and ruin to despise,

To scatter plenty o’er a smiling land,

And read their hist’ry in a nation’s eyes,

Their lot forbade: nor circumscrib’d alone

Their growing virtues, but their crimes confin’d;

Forbade to wade through slaughter to a throne,

And shut the gates of mercy on mankind,

The struggling pangs of conscious truth to hide,

To quench the blushes of ingenuous shame,

Or heap the shrine of Luxury and Pride

With incense kindled at the Muse’s flame.

Far from the madding crowd’s ignoble strife,

Their sober wishes never learn’d to stray;

Along the cool sequester’d vale of life

They kept the noiseless tenor of their way.

Yet ev’n these bones from insult to protect,

Some frail memorial still erected nigh,

With uncouth rhymes and shapeless sculpture deck’d,

Implores the passing tribute of a sigh.

Their name, their years, spelt by th’ unletter’d muse,

The place of fame and elegy supply:

And many a holy text around she strews,

That teach the rustic moralist to die.

For who to dumb Forgetfulness a prey,

This pleasing anxious being e’er resign’d,

Left the warm precincts of the cheerful day,

Nor cast one longing, ling’ring look behind?

On some fond breast the parting soul relies,

Some pious drops the closing eye requires;

Ev’n from the tomb the voice of Nature cries,

Ev’n in our ashes live their wonted fires.

For thee, who mindful of th’ unhonour’d Dead

Dost in these lines their artless tale relate;

If chance, by lonely contemplation led,

Some kindred spirit shall inquire thy fate,

Haply some hoary-headed swain may say,

“Oft have we seen him at the peep of dawn

Brushing with hasty steps the dews away

To meet the sun upon the upland lawn.

“There at the foot of yonder nodding beech

That wreathes its old fantastic roots so high,

His listless length at noontide would he stretch,

And pore upon the brook that babbles by.

“Hard by yon wood, now smiling as in scorn,

Mutt’ring his wayward fancies he would rove,

Now drooping, woeful wan, like one forlorn,

Or craz’d with care, or cross’d in hopeless love.

“One morn I miss’d him on the custom’d hill,

Along the heath and near his fav’rite tree;

Another came; nor yet beside the rill,

Nor up the lawn, nor at the wood was he;

“The next with dirges due in sad array

Slow thro’ the church-way path we saw him borne.

Approach and read (for thou canst read) the lay,

Grav’d on the stone beneath yon aged thorn.”

THE EPITAPH

Here rests his head upon the lap of Earth

A youth to Fortune and to Fame unknown.

Fair Science frown’d not on his humble birth,

And Melancholy mark’d him for her own.

Large was his bounty, and his soul sincere,

Heav’n did a recompense as largely send:

He gave to Mis’ry all he had, a tear,

He gain’d from Heav’n (’twas all he wish’d) a friend.

No farther seek his merits to disclose,

Or draw his frailties from their dread abode,

(There they alike in trembling hope repose)

The bosom of his Father and his God.

Multimedia

“Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard” read by Tom O’Bedlam

A critical examination by Professor Belinda Jack from Gresham College, London, April 2015

Suggested activities

Language and Meaning

1. Both the opening stanza and the closing ones are immediately concerned with the poet himself. What does this device suggest you?

2. Stanzas from 1 to 4 make up both the time and the setting of the poem. Find the adjectives, nouns and verbs used by the poet and express their connotations.

3. Death is the leitmotiv of the whole composition. Find the words related with it and their connotations.

4. What is, according to the text, the function of the grave?

5. Find the animals and the trees in the text together with their possible connotations so as to move to the symbolic level.

6. The human beings in this poem are divided into two main social categories: rich and poor. How does the poets describe them?

7. Try and make an inner portrait of the poet as he himself is seen in the closing stanzas and, particularly, in the Epitaph.

8. Work out the religious sense of the poem.

Extension

1. Make a comparison, both as to form and content, between Gray’s Elegy and the following ode by Alexander Pope:

Ode on Solitude

Happy the man, whose wish and care

A few paternal acres bound,

Content to breathe his native air

In his own ground.

Whose herds with milk, whose fields with bread,

Whose flocks supply him with attire;

Whose trees in summer yield him shade.

In winter fire.

Blest, who can unconcernedly find

Hours, days, and years, slide soft away

In health of body peace of mind,

Quiet by day.

Sound sleep by night. study and ease

Together mixed, sweet recreation,

And innocence, which most does please

With meditation.

Thus let me live, unseen, unknown;

Thus unlamented let me die;

Steal from the world, and not a stone

Tell where I lie.

2. Analyze Gray’s and Foscolo’s different attitudes as to the grave.